The alchemy symbols on the outer walls of the Lash Miller Building at the corner of St George and Willcocks Streets are a striking feature of the north-east entrances to the Department of Chemistry.

While the symbols, together with their old French descriptors, are summarized in a somewhat inconspicuous poster in the lobby, there is no document that gives the English meanings and provenances of the symbols. In view of the significant role the alchemy symbols played in the early days of chemistry, I have prepared this synopsis to provide additional information on these singular Lash Miller decorations.

There were some symbols that were not straightforward to identify from my own searches. Accordingly, I sought help from a number of sources, including the members of the Department. I was astonished, but very pleased, by the widespread enthusiasm my queries elicited, showing that there was extensive interest in the topic. I would like to thank everyone who responded for their multiple inputs, which have been extremely helpful and which I have incorporated where appropriate. There are too many to acknowledge each individually so here I thank all collectively, but no less sincerely for that. However, I would like to express my particular gratitude to Professor Rob Batey for his support and invaluable input, and to David Stone and Armando Marquez for their painstaking contributions in providing the high resolution images of the symbols guide posted in the Lash Miller lobby from which the figure reproduced below was derived.

There may well be further clarifications or error corrections needed, and I would be grateful if viewers would email these to me.

Bryan Jones

University Professor Emeritus

bryan.jones@utoronto.ca

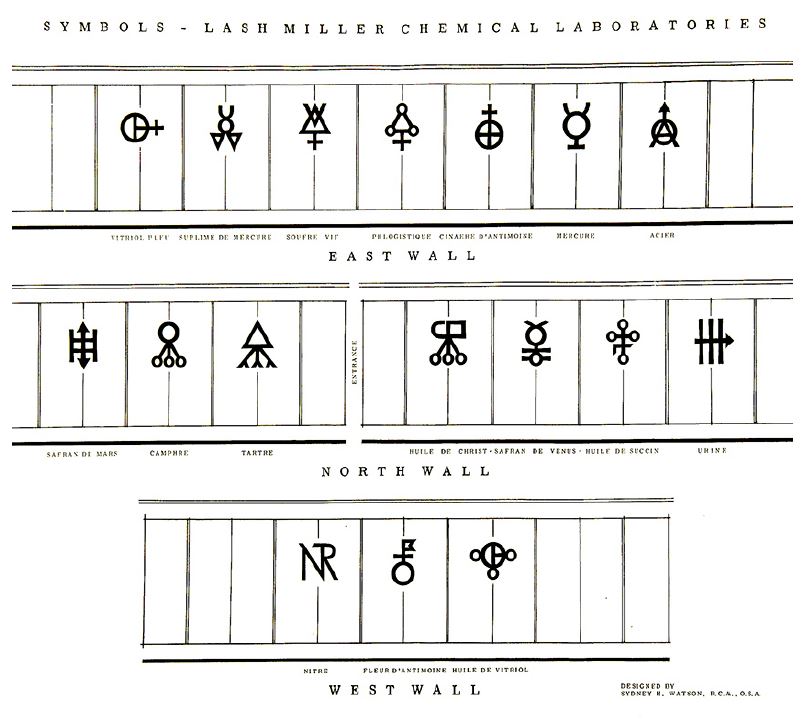

The information poster in the Lash Miller Lobby provided by the architect in 1963 is shown below. They, and their old French names, are reputed to be from the 17th century. However, at least one of them (Huile de Christ) has been dated by an expert authority as being no earlier than 1750.

Because it enables searching for symbols for element/compound, etc. names via detailed alphabetical indices, Symbols.com provides a useful complement to other image-only alchemy symbol sites, such as Google Images Search.

The Lash Miller Alchemy Symbols

East Wall

Cupric Sulfate (Pentahydrate)

Literally Blue Vitriol – used as a fungicide. Also known as bluestone. Vitriol was the compound obtained by distillation of various sulfates and that we now know is sulfuric acid. As long ago as 1500 BCE, the Egyptians used blue vitriol, and also green vitriol (ferrous sulfate), in the treatment of various diseases and ailments.

Mercury Sublimate – Mercuric Chloride

Mercury compounds were known to the Chinese and ancient Egyptians, and used therapeutically by the Greeks in the 1st century CE. The medicinal value of mercuric chloride was recognized in Arabia soon after this but, being toxic, was used only topically as an ointment in the treatment of syphilis, together with non-toxic oral preparations of mercurous chloride (calomel), especially during the European outbreak of syphilis in the 15th century.

Natural Sulfur

This was widely known from antiquity from its volcanic origins, and from iron pyrites. It was used medicinally from ancient Egyptian times, in the1st century CE in Greece as a fumigant, and in traditional Chinese and early European medicine. It has been postulated that its medical benefits were due to its slow oxidation to sulfite – a mild antibacterial agent.

Phlogiston

This was postulated in 1667 by Becher, and clarified by Stahl in 1703, to be contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion, in an attempt to explain burning processes, which we now classify as oxidations. This theory ran into problems when it was shown experimentally that flammable metals such as magnesium gained mass on burning even though they were supposed to have lost phlogiston in the process. The theory ran into increasing dilemmas of credibility as experimental chemistry developed, requiring its devotees to create increasingly irrational modifications to the theory to account for the new results. The phlogiston theory gradually lost its adherents, which even included Joseph Priestley, but retained its dominance until in 1778 Lavoisier demonstrated that combustion required oxygen. This signaled the end of the phlogiston era.

Cinnabar of Antimony

This was a sublimate prepared by heating together the antimony ore stibnite (composed of antimony trisulfide) with corrosive sublimate (mercuric chloride) in a retort. First, butter of antimony (antimony trichloride) distilled over, and at higher temperature a red sublimate. This red sublimate was called cinnabar of antimony, but was in fact regular cinnabar, which is mercuric sulfide, the familiar red pigment vermillion. We are grateful to Professor Lawrence Principe (Johns Hopkins University) for his detailed clarification of the initially confusing meaning of this symbol. [The legend in the Lash Miller lobby mistakenly labels this as Cinaere d’Antimoine, but the word cinaere does not seem to exist in French and is evidently a misprint for cinabre. While cinaere could be from the Latin cinere = ashes, with the dipthong-e of old French, this does not lead to a reasonable alchemical interpretation].

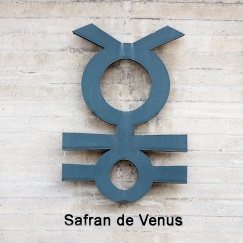

Mercury

Liquid mercury was known to the ancient Chinese, Egyptians, Greeks. Romans and Hindus. It was used in medicine, usually as its chloride derivatives, as an insecticide, poison, or disinfectant, or topically in its toxic mercuric form, and orally as a purgative as mercurous chloride (calomel).

The element itself was also known as quicksilver, in recognition of its shine and mobility. Likewise, these were characteristics of the Roman god Mercury, hence the alchemical use of the planet’s astrological symbol for the metal. It was designated as one of the tria prima (three primes) of alchemy by Paracelcus (1493-1591), as the fluid connection between the High and the Low. While the metal itself does occur in nature, its largest natural source is the red ore cinnabar (mercuric sulfide), from which it is obtained by roasting in air.

Steel

The method of making steel by using carbon to reduce iron ores was undoubtedly discovered accidently in iron preparation, as a result of carbon contamination from prehistoric charcoal fires in early iron ore smelting. The ancient Egyptians were skilled in metallurgy and made iron objects from meteorites in the 4th millennium BCE, and from iron ore by the end of the 2nd millennium BCE. However, it was in India that steel making became advanced by the 6th century BCE (Wootz steel) and by 200 CE high quality steel was being produced. By the 1st century BCE the Chinese had discovered the secret of steel and in 5th century they adopted the Wootz steel methodology.

In the 11th century they discovered how to use coke in place of charcoal in smelting. The switch from charcoal to coal as a fuel was pioneered in Roman Britain in the 2nd century. In Greece, Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE) understood the difference between steel and the softer wrought iron. The medieval Islamic world had also developed similar skills by the 11th century, with Damascus steel being highly prized from 900 CE to 1750 CE . In contrast, European steel expertise did not develop until the 17th century. Blast furnaces existed in China in the 1st century CE, in Belgium in the Middle Ages, and in Britain by the 15th century. (It should be noted that blast furnaces as old as 2000 years have been reported in Tanzania).

In 1709, in Britain, Abraham Darby (re)discovered how to convert coal to coke. Substitution of coke for charcoal in blast furnaces resulted in much increased efficiency and economy. By the mid-19th century Henry Bessemer showed that introducing oxygen could burn off some of the carbon in cast iron, allowing for large-scale production of cheap steel. The current oxygen-based process was introduced in the mid-1950s and now accounts for ~60% of steel production.

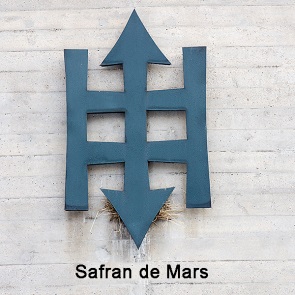

Ferric Oxide

Literally Yellow of Iron. In alchemy, the use of the astrological symbol for Mars was used for iron, iron being regarded as a metal of strength and force, and Mars being the classical planet of energy and force. Ferric oxide was produced by roasting iron ore, and as long ago as 1500 BCE the Egyptians used iron oxide (powdered rust) to heal wounds.

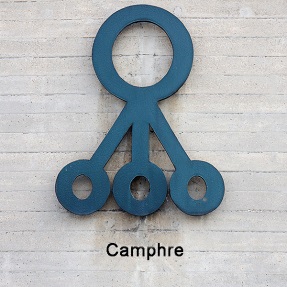

Camphor

The name is derived from the French camphre (as in the symbol name shown), which itself comes from the medieval Latin camfora, the Arabic kafur, Sanskrit karpura, and ultimately from old Malay kapur barus. Barus was the Sumatran (Indonesian) port used by traders from India and the Middle East to ship the dried resin from the camphor trees native to that region. Camphor has a long history of use. The ancient Egyptians employed it in mummification, and in ancient and medieval Europe and Arabia it was used as a culinary ingredient and for flavouring. It was utilized in ancient Sumatra to treat sprains and inflammation and, in Europe in the 18th century (in admixture with opium), as an antitussive agent and analgesic. It is still used for flavouring, and as a weak, cooling, anesthetic and cough suppressant.

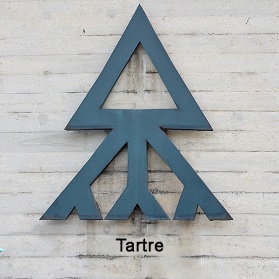

Tartar

Potassium hydrogen tartrate (potassium bitartrate) was originally derived from grapes. Tartar was known to the Arabian alchemist Jabir ibn Hayyan in 800 CE. The modern preparation was developed by the Swedish pharmaceutical chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele in 1769. (Scheele was an largely uncredited chemist who discovered several metals and organic acids before others, and was the first to discover oxygen (although Priestley published first) and chlorine before Humphrey Davy). Oil of tartar (a concentrated aqueous solution of potassium bitartrate) is an old preparation applied as a cosmetic at least up to the 13th century, and is still used for cleaning cloth and rusty metals, as well as in food preparation. Tartaric acid itself is also used in food and drink preparation, and in 1832 played a key role in the discovery of chirality by Biot. This was followed by the first production of (-)-levo-tartaric acid, via hand separation of (+) and (-)-ammonium sodium tartrate crystals, by Pasteur in 1847.

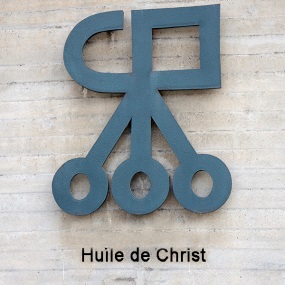

Oil of Christ

This is a very rare symbol that has appeared, without any description of properties or composition, in only one of the numerous alchemy charts viewed so far.

Its alchemical significance remains unclear at this time. We have consulted Professor Lawrence Principe (Johns Hopkins University) who has looked into this dilemma in depth. The following interpretations of what this alchemical symbol could mean incorporate his detailed scholarly analyses, for which we are very grateful.

The symbol appears to be very late addition to the list of alchemical symbols, certainly dating no earlier than 1750. Deciphering the symbol’s components provides clues to its possible meaning in that the three circles clearly come from the standard symbol for oil, and it is plausible that the top part could be interpreted as “CP”, signifying Christi Palmi . The symbol would then represent Oleum Christi Palmi - Oil of Palm of Christ, which is castor oil, widely used in the distant past as a healing agent.

The first recorded medicinal use of castor oil was by the ancient Egyptians in 1550 BCE in treating eye problems. Subsequently, it was known to the ancient Greeks as kiki and to the Romans as Palma Christi - the leaves of the castor oil plant being thought to resemble the Palm of Christ. Later, in Europe it was used in topical compresses to relieve inflammation, and in the 17th century as a bowel purgative. These uses persisted at least up to the mid-20th century. The therapeutic benefits of castor oil have been attributed to its major component, ricinoleic acid, and also somewhat to its minor component, oleic acid. Care must be taken to use only the cold pressed oil from castor beans since the residual mash contains the deadly toxin ricin, for which there is no antidote.

A non-medical use of castor oil was as a lubricant, especially for aircraft engines in the early 20th century. One lubricating oil formulated with castor oil was pioneered by a company founded in 1899 in London by Charles Wakefield. This oil was promoted under the name Castrol. The Wakefield company went on to become one of the world’s largest lubricating oil companies, and eventually renamed itself as Castrol Ltd.

While castor oil seems the most reasonable chemical match for this symbol, there are other less likely possibilities, such as that it represents Oil of Crystal. For centuries, healing properties have been attributed to preparations of various inorganic crystals or minerals in oils such as olive oil. There do not appear to be any scientific bases for these beliefs.

Perhaps least likely is the literal translation of Huile de Christ as Oil of Christ, for which term extensive searching has revealed nothing of medicinal benefit. It could be the ancient anointing oil used in the ordination of Jewish priests and consecration of temples. This was olive oil containing perfumes such as myrrh, different cinnamons (sweet and cassia), and Kaneh bosem (an aromatic cane growing in the Holy Land).

Alternatively, it could refer to the oil used to anoint the body of Jesus after the Crucifixion, reported to be the perfume nard. (Nard is an aromatic oil derived from Himalayan plants of the lavender family).

Yellow Copper – likely cuprous oxide

Copper compounds, including copper oxide, have been used medicinally since the second millennium BCE in Egypt, in ancient Greece since the 1st century BCE, by the Romans in the 1st century CE, in the 10th century in Persia, and in Europe up to the 20th century

Cuprous oxide is currently a component of some ship antifouling paints.

Oil of succinate

Succinic acid, spirit of amber, was obtained many centuries ago by distillation of amber.

Baltic amber has unique properties that have long been exploited in the treatment of a variety of medical conditions, including by Hippocrates (460-377 BCE), the father of medicine. Baltic amber contains up to 8% of succinic acid and it is now recognized that it is this component that is responsible for its beneficial properties. Even today, succinic acid is a key constituent of many medicines.

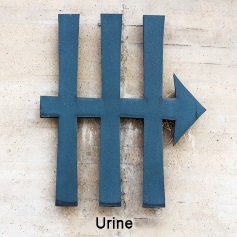

Urine

Urine has been used in medicine for millennia. In ancient Greece, Pliny the Elder recommended fresh urine for the treatment of sores, etc. while in the 17th century the father of chemistry, Robert Boyle, recommended the drinking of fresh urine for certain ailments. Thankfully, nowadays we have alternative forms of medication. Boyle also noted its value in dyeing and as an invisible ink

Urine was also the first source of white phosphorus, prepared by the German alchemist Hennig Brand in1669 by heating dried urine in a retort. The fumes evolved were spontaneously combustible, but when collected in a sealed jar gave a white solid. Since this material glowed in the dark Brand named it phosphorus, from the Greek word phosphoros for “light bearer”.